(This post has been transferred from ‘Newcastle Government Domain’ WordPress site- originally posted 14 March 2017)

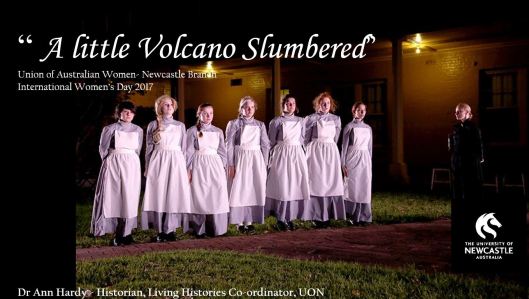

International Women’s Day was celebrated by the Newcastle Branch of the Union of Australian Women on 3rd March 2017 at Charlestown Bowling Club with a talk by Ann Hardy. The topic was the Newcastle Industrial Girls School (1867-71) an institution that in August 2017 commemorates 150 years.

The girls’ school was at what is known as the James Fletcher Hospital (JFH) a site that continues as a mental health site, managed by Hunter New England Mental Health (HNEMH). The use as a girls’ school was the most controversial of all the uses at the site.

“I became interested in this historic mental health site in Newcastle when I worked there as a Social Worker in the 1990s, it was a completely new environment. Despite the mental hospital taking up almost a whole block in the CBD, it remains hidden, the long association and stigma of mental health, has in fact been its saviour!” Ann Hardy

While working at the JFH during the late 1990s I was shown some old mental health case books from 1871, the first patient was John Buckley. The experience of looking, touching and smelling an archive stayed with for many years – years later I searched for these records, by this time they’d been transferred to State Records NSW.

“In 2004, I took leave from work to study heritage site management, I’d realised that many heritage sites in Newcastle were vulnerable, very little histories had been written about them- and I was particularly concerned about the JFH. I became involved in heritage debates in the city, but my focus was at the JFH site– history there was mostly absent. History is the evidence needed to fight heritage battles, and historical evidence is crucial in arguing heritage significance.” Ann Hardy

Historical Timeline

1801 – 1804 Centre of local administration during penal settlement, contained Government House and gardens

1814 – Wallis Shaft Early working coal mine

1844 – British Military Complex 1853

1860- Newcastle Volunteer Rifles

1867-71 Girls Industrial school and Reformatory for Girls

1871 – Asylum (originally named ‘Newcastle Asylum for Imbecile and Idiots’), the first regional Government asylum, the first of its type in Australia & third Government institution of its type in the world.

Australia has a deep embedded history associated with providing health care

The NIS was only there for a very short period of four years, and another institution also opened during this period, the reformatory for girls (1869-71), it was a much smaller institution.

Research of individual girls undertaken by historian Jane Ison who has written biographies for over 190 girls (SEE NIS wikidot)

Why was the school established?

The Industrial School was established to care for children deemed ‘at risk’, usually neglected or abused, whereas the Reformatory was for girls who had committed offences.

The Industrial school and Reformatory acts came about in 1866, and in the following year legislation was implemented at the newly established Newcastle institutions, first admissions occurred in August 1867. Most of the children came from Sydney, and other parts of regional NSW. Some had been caught up in a cycle of poverty and neglect – a problem that had been spiraling out of control for decades in NSW.

Some of the reasons children were admitted included:-

- transferred from existing institutions

- homeless

- taken away from their parents if the environment was deemed to be unsafe

Other children were admitted to the school if their mothers required institutional care.

There were age restrictions for children admitted to orphanages, and it was not until the Industrial Schools Act and Reformatory Act (1866) that children over the age of 10 could be legally admitted to government institutions for their care and protection.

Although these new acts adopted newer educational models, in reality a culture of management from the old penal system continued. Legislation for these girls was drafted by former naval personnel, because the original idea was the management of boys through a nautical program, not girls. Boys were put on the ship ‘Vernon’.

Under the new acts authorities could detain, provide training and accommodation for children under the age of 16.

Vulnerable children living in unstable households, and having no extended family were identified by constables in Sydney who compiled a list of these children ‘at risk’. On the list were sisters Eliza and Theresa Hanmore, aged 15 & 7. They were 2 of 12 girls admitted by court order, to Newcastle in 1867 and subject to the control of the Superintendent who became their legal guardian until they were 18.

Some of the girls were released early and returned to their families, or after twelve months, were apprenticed out. Of those who returned home, constables regularly visited to check on their welfare.

In 1868 Henry Parkes visited the Newcastle school and in a speech encouraged the girls to make the most of their circumstances, urging them to look for opportunities that would advance their lives:-

“I want you to look upon life hopefully and at the same time try to understand your duty…It should not be forgotten that you are supported here at great cost to the country. I hope your obedience to those placed over you, and your general good conduct, will prove that you appreciate the benevolent intention of the Legislature in making this provision for your permanent welfare.”

Although Parkes emphasised their care was at a significant cost to the government, he also tried to empower them, by saying,

“one day you will make heads of families, possessing property and influence and enjoying the respect of good men and women.”Henry Parkes 1868

However the girls were very testing towards the authorities who found them extremely difficult to manage. Their new home was unfamiliar – the institution was purpose built for men, not children who were housed in the unaltered military buildings- was a very male environment.

THEIR DAILY ROUTINE WAS VERY STRUCTURED.

– 5.30AM WASHED AND DRESSED

– 7AM BREAKFAST

– 8.00 AM ‘INSPECTION’ OF ROOMS

– 15 MINUTES OF PRAYER BEFORE 9AM EDUCATIONAL CLASSES

– 12.00 FURTHER RELIGIOUS INSTRUCTION AT MIDDAY.

– 12.30 LUNCH

– SEWING FROM MID-AFTERNOON UNTIL DINNER AT 5.00 PM.

– 6.30 PM MORE PRAYERS THEN GIRLS CONFINED TO THEIR ROOMS

– SATURDAYS GENERAL CLEANING AND BATHED IN THE AFTERNOON.

– SUNDAY MORNING CHURCH – AFTERNOON FURTHER RELIGIOUS INSTRUCTION AT SUNDAY SCHOOL.

There was very little time for fun, no attempt to integrate the girls into normal public life.

The Industrial School legislation was harsh and punitive and the Superintendent had significant powers, they had full ‘custody and control’, a child could be placed in complete confinement for up to 14 days. This was given to the girls who escaped from the institution.

Whereas the Reformatory legislation gave authority to place girls under the age of 18 in ‘strict incarceration’, but this was at the local gaol for up to 3 months. This is what happened to the children who absconded from the reformatory (they were sent to Maitland or Newcastle Lock Up).

In total 186 girls passed through the Industrial School, just 6 were admitted to the Reformatory, and only 30 of 186 (only 16 percent) were apprenticed out.

The majority of the girls were aged 14 – 15 (a vulnerable age as identified by list compiled by Constables in Sydney)

Riots and Escapes

There were many riots and escapes. The girls’ were notorious for their extreme bad behaviour. Their antics reported regularly in newspapers across the nation. Riots started at the school early 1868 not long after the institution opened and continued until nearing its closure.

Matron King witnessed several incidents, on one occasion, the girls told her they saw a man or a ghost under a bed, they shrieked to get the attention of locals, however many in the community disliked the girls and instead had sympathy for the Matron who they believed was doing her best – girls were ostracized by the community.

One of the worst riots occurred while Superintendant Lucas was in charge, it was triggered after 10 girls broke out of the military cells from where they had been locked up. Armed with weapons ‘in the shape of brick bats’, stones and ‘billets of wood’ the girls went on a rampage, neither staff nor police were able to take control and reinforcements were sent for from Sydney, they stayed 3 months.

Senior Sergeant Lane (who came from Sydney), later said he had

“…never witnessed anything like this before, or during my 10 years on Cockatoo Island with the worst of criminals”.

Another incident occurred where it was reported a ‘little volcano slumbered’, there were outbursts of rioting, the girls had waited until the Superintendant went to Sydney to mount their protest, they’d heard about the impending closure of the school and armed with iron bedsteads, they broke through dormitory doors and got away over fences into neighbouring streets. Thirteen of them were captured and sent to the lockup. 11 of them were confined, at the school on bread and water. The 4 ringleaders were charged with willfully destroying government property and were transferred to Maitland Gaol for a month.

One of the girls involved in the riots was Mary Ann Meehan, she was a serial offender. One episode involved her escaping from the school disguised in Mrs. King’s clothing, she was recaptured and sent to Maitland Gaol. She also threw a cup of water and pound of bread at the Matron, and for this spent time in solitary confinement. She was incarcerated several times but remained undeterred by the harsh treatment and continued to act defiantly.

Eventually she was transferred to Cockatoo Island where she attempted to burn down the dormitory. It was a serious charge, courageously she represented herself at the trial. She was an intelligent and articulate girl, the magistrate was so impressed that she’d taken it upon herself to

“cross-examine the witnesses with an astonishing display of forensic ability” providing “. . . a very lengthy and plausible address to the Court that was artfully intermingled with a harrowing description of the treatment she had encountered at the old Reformatory at Newcastle.”

She also alleged she had been falsely detained because she was over age of 18, and she complained that her hair had ‘violently’ cut.

She stated that going to Maitland gaol was preferable to being locked up in the reformatory, and was willing to serve the remainder of her time (6 months) at Maitland gaol – highlighting just how harsh punishment was at the reformatory compared to the adult prison.

The school eventually closed in 1871, and the Girls were transferred to Cockatoo Island (Biloela) on Sydney Harbour, then later to the Parramatta Girls Industrial School (also known as ‘Parragirls’)

The school had failed for several reasons:-

- Inadequate and untrained staff, lack of proper resources. The complete anarchy at times and the distance from Sydney was problematic, authorities were clearly unable to deal with the series of riots.

- The girls were not properly ‘classified’ – mix was toxic (delinquent girls with girls who had been abused and neglected).

- Many in the community simply disliked the ‘girls’, the stigma and association with prostitution isolated them.

- No attempt to integrate the girls into the community (apart from the few apprenticeships offered) there was very little socialisation.

- Result was a dysfunctional institution- things didn’t change when they went to Cockatoo Island.

Despite all the faults of this institution, I believe there were genuine attempts by the NSW Government to care for these girls, certainly not ideal, but considering the context (Minimal funding and lack of other caring institutions, and other social and family support) authorities did their best, intentions were well meaning – it was perhaps the personnel who took advantage of the legislation and harsh penalties.

On reflection – has care of children improved?

Recent 4 corners program “Broken Homes” late 2016 was very confronting, about the frontline of Australia’s child protection crisis, there remains a level of isolation for many children in permanent care today. Government care is at arm’s length- checks and balances are becoming blurred when care is increasingly contracted out and privatised.

What the girls at the NIS can teach us is that although the focus was on education and training, it is likely the girls’ experiences is what made an impact, hopefully some of them formed friendships and became stronger and more resilient and they succeeded in life.

Lifelong learning is about lessons in life “school of hard knocks” and experiences we learn from, and take with us into new situations – and new environments.

Working with people and communities are all wonderful lessons in life, and just as valuable as formal education. This is particularly relevant today where collaboration, creativity and new innovative ideas are encouraged – life experience and practical knowledge can be valuable.

Other Sources

Newcastle Industrial School for Girls. By Jane Ison http://nis.wikidot.com/

Hardy, Ann ‘. . . here is an Asylum open . . .’ Constructing a Culture of Government Care in Australia 1801- 2014, University of Newcastle (2014) – Thesis UON.

Stories in Our Steps Uncovers Watt Street’s History, The Star Newspaper. 30 March 2015.