CASE 14: WHEN I GET BACK TO PORT PIRIE

Thomas Batterham cursed the growling stray dog circling his sulky and nipping at his horse’s heels. The dog had been attacking cyclists and startling horses for weeks around the Lookout on the new Cardiff-New Lambton Road.

It was around 3:30 pm and Batterham was hurrying to a meeting at his small orchard business up the road in Cardiff. The horse remained still while Batterham scared the mange terrier off with his buggy whip. He watched it slink away along the road just as a blue suited young man wearing a wide felt hat appeared out of the bush, carrying an uncocked, double-barrelled gun.

Batterham nodded and asked him casually if he was ‘looking for a shot?’

The young man grinned before politely declaring ‘I am going down there looking for some’ pointing to the gully at the side of the road.

Batterham pointed to the dog strolling down the road ‘there is one bastard right now’.

‘Do you want him shot?’

‘Yes, he will be killing somebody.’

The young man walked in front of Batterham’s trap, coolly assumed position, called out the dog and fired. The dog dropped lifeless on the road.

‘I aimed at the back of his front leg.’

‘Yes,’ and you got him there, too. It was good shot.’

Both men said their good days and parted in opposite directions.

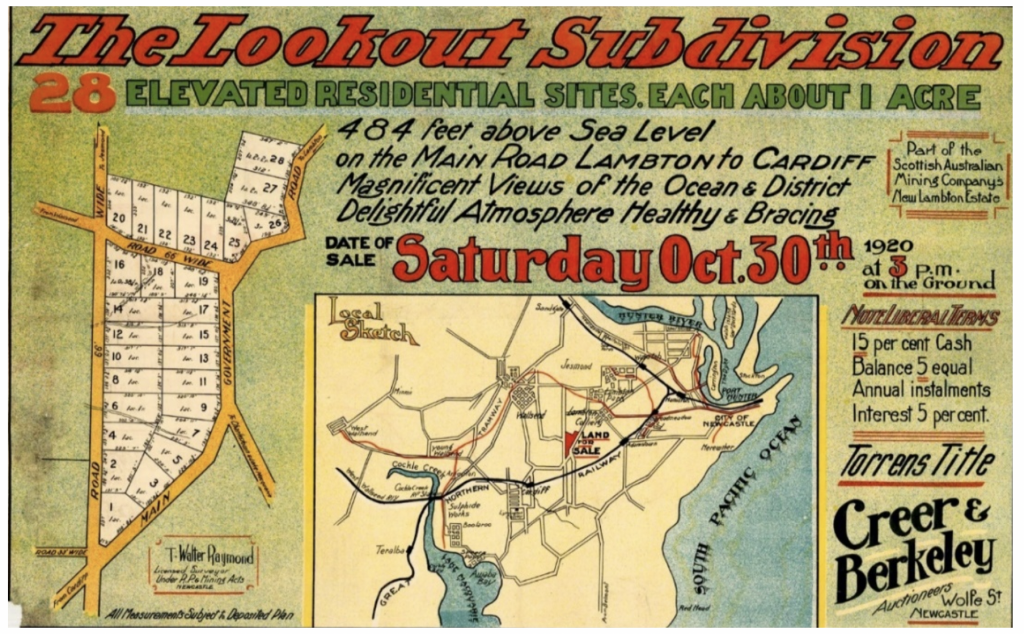

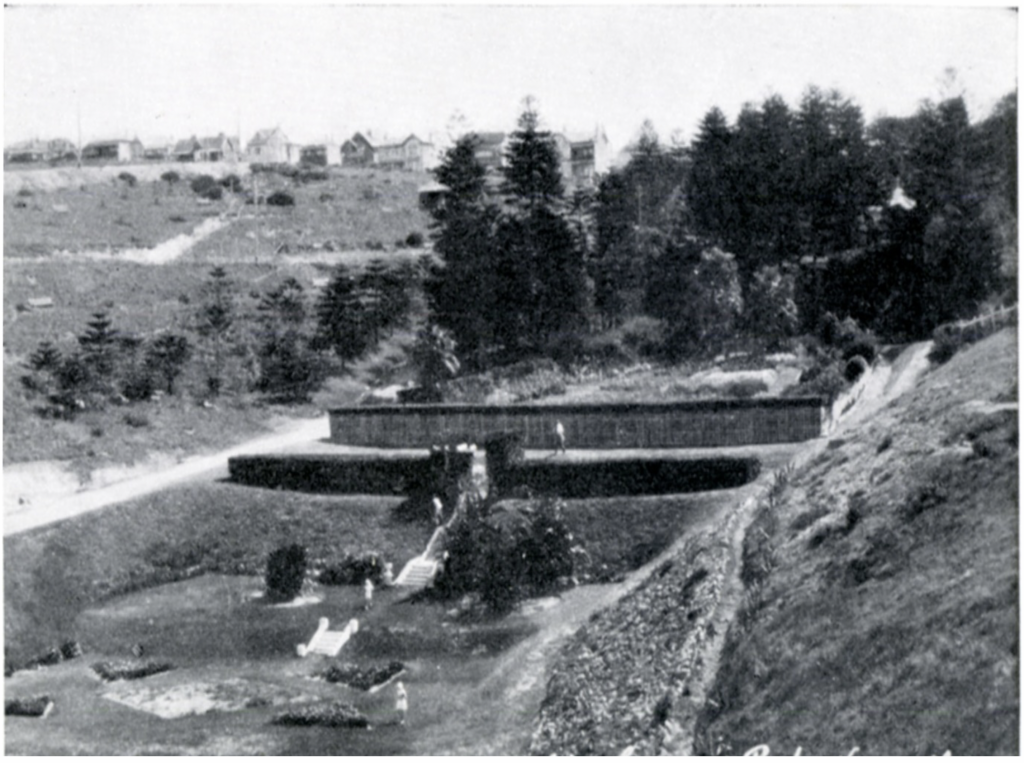

The recently constructed Lookout Road between Cardiff and New Lambton was opening up Newcastle’s Western hills. Viewing platforms provided impressive South Pacific panoramas. Not long after the dog’s demise, a businessperson named Lyne stopped his car in the tree shade of one of the viewing platforms. Just as he lit a pipe gunshot rang out from the bush. Buckshot ricocheted off the car’s body, causing Lyne to choke on tobacco smoke and manically start his engine. In the frenzy to get moving, he swerved dramatically around Mo Lun, a local Chinese market gardener who was meditatively heading down to New Lambton with a full cart of produce. The double-lucky Lyne rattled off with his eyes on the road ahead, too frightened to look back and worry about the Chink.

At about 4:30 pm that same day of 20 January 1920, New Lambton police were called to Lookout Road. A deep wheel line down an embankment directed them to Mo Lun’s cart, which had overturned after striking a heavy eucalypt on the way down. The owner was facedown among scattered branches and shining fruit. His autopsy would later reveal shot marks on the left side of his face, including four distinct perforations of the ear, and more shot in his left shoulder. It suggested Mo Lun was facing his shooter from at least ten yards distance (this reasoned from the scattered nature of the shot in his body). Another separate wound at the back of his neck had severed the spine and fractured the base of his skull. The grains of shot suggested close range, further confirmed by some cartridge wad found embedded in the neck. This last injury was later given as cause of death.

One member of the small crowd that met the police that afternoon was John Cooper. He regularly walked to Lookout Road from his home in Mayfield to soak up its nerve-soothing, ocean view. The sight of the poor devil lying among the still shining fresh fruit and veg instantly triggered terrible and frightening memories for the shell-shocked war veteran. He could not bring himself to help, but forced himself to wait and talk to police for what it was worth.

Inspector Detective Ramsey was called up from Sydney to formulate evidence and witness statements. He arrived to the increasingly unsettling rumour that Mo Lun was bailed up by bushrangers for a 20-Pound note. Residents of the Lookout estate were now fearful that killers roamed the surrounding bushland, darkening the idyllic promise of their new, modern life on the hill.

The fact Lun’s money and pocket watch was found on his person in reality suggested something other than random robbery. This was reinforced by the respected Aboriginal tracker Paddy Marsh, who was called in from Queensland, and found a few stills and a couple disused hunting camps, but no evidence of bushrangers. In his opinion they should elsewhere for the shooter.

A week after the shooting blood stained fruit and vegetables memorialised the place of death. One local paper proudly announced none of the residents had helped themselves. Witness taking pointed to a mysterious blue suited boy as the main person of interest. Multiple witnesses had seen him striding carefree along Lookout Road the afternoon of January 20. Their combined statements created a picture of a clean-shaven, fair skinned, thin young man with a beakish nose. All mentioned his unique gait, which one witness described as determined but ethereal.

The urgent search for the young man was complemented by forensics. Ball shot pulled from dog’s forelegs matched that found in Mo Lun. An exploded blue cartridge case stamped Winchester New Rifle. No. 12 was found about 80 yards from Mo Lun’s body, while another was lying on the ground near where Batterham was pretty sure the terrier had been shot. A wad found on the ground also colour matched the piece embedded in the back of Mo Lun’s head.

Despite initial momentum of the case, police admitted after a week that finding the blue suited suspect had reached a point of “nowhere”. Just as the arduous check of hotels, trains and the port was to begin, police caught an astonishing break.

On January 30 a milk vendor was rabbiting with his dogs on Shepherd’s Hill behind King Edward Park. In a gully crevice, one of them sniffed at a hole covered by tin. Within it was a double-barrelled shotgun, a box of shotgun cartridges, a box of revolver cartridges, a blanket, and work clothing covered in paint. Plain clothes Constable McCarthy and Inspector Ramsay attended. Ramsay removed the gun and cartridges for testing, while McCarthy staked out the site from a park bench.

About 3 the following afternoon a young male sidled down the hill ‘like a bloody mountain goat’, McCarthy thought. He stood opposite the hole for a few minutes, scanning the area with feigned indifference. After briefly sizing up McCarthy (on his seat and blowing cigarette smoke dismissively at an imaginary annoyance in the air) the young man pulled the tin away from the crevice to fiddle with the contents. Taking nothing he replaced the tin and walked deftly towards King Edward Park. McCarthy paced step for step behind him at a distance. After some cat and mouse near the Park’s rotunda, McCarthy confronted the young man:

‘I want to know who you are and what you were doing round Shepherd’s Hill.’ The young man gave no answer.

‘I saw you there. Can you tell me whose clothes and gun they are?’

‘What clothes?’

‘The clothes in the crevice.’

The young replied that his name was Charles Poole, he was a painter from South Australia, he was staying at The Exchange Hotel, and had his meals elsewhere.

‘All the clothes and boots at the hill are besplattered with paint’

With an unexpected, sudden admission Poole said ‘Yes, they are all my properly.’ He also admitted to owning the gun and ammunition.

McCarthy asked Poole why he hadn’t kept them all at the Exchange.

‘I left them in the crevice because I was about to clear out to Sydney in a few days, I owed money at the hotel, and they would be easier to get at there,’ he replied.

Taken to Newcastle police station for questioning clippings from a recent Newcastle Sun were found on Poole’s person, showing photographs of the Mo Lun crime scene.

Poole claimed knowing Mo Lun back home in Port Pirie, so he wanted to share the photos with people there. He said he had never been on Lookout Road, or know where it was, He had not shot a dog there. On the 20 January he was working until 5 pm, painting walls.

Once in custody Poole’s explanations failed to agree with each new contradicting detail put to him: Poole admitted to having bought a Winchester after work on the day of January 20 to shoot rabbits. Witnesses remembered someone resembling Poole purchasing a gun and cartridges on that morning. He agreed to having been on Lookout Road and shooting the dog after Batterham confirmed him from a line up. Two young boys playing the bush recognised Poole as the man they saw under a tree drinking from a whiskey bottle that same day. No, he didn’t know Mo Lun (who had never been to South Australia, but was well known about New Lambton, only leaving the place twice in the last 5 years to visit his wife and three children back in Canton). Poole said he lied about being in the bush with a shotgun on the day, because he was afraid of being connected with the shooting of the Mo Lun.

The Exchange confirmed Poole was scrupulous paying advance rent for his hotel room. They considered him polite and charming with everyone. William Lahiff, master painter, hired Poole on January 12 from the Labour Bureau. Poole worked from January 13 to January 19 before the young man told Lahiff he was leaving Newcastle to travel south.

The sports department at Mick Simmons store confirmed they carried the popular Winchester shotgun found in the rabbit hole. Examination of the gun revealed the left barrel had burst due to a defective firing pin and ejector. This produced unique marks on the fired cartridges. Tests were done comparing those fired on January 20 at Lookout Road, with those taken from Shepherd’s Hill. The unique marks matched, along with the cartridge type and wad colour.

Poole’s increasingly ludicrous responses validated the evidence collected against him. He was charged with Mo Lun’s murder. At his trial the prosecution began by reading Charles Poole’s original arrest statement to the court:

‘I do not know where New Lambton is, and I did not shoot a dog for anyone. He said he went out shooting two days after he bought the gun. He went out for a walk, but did not know in what direction. He was asked where he took the gun from. He said he took it from the hotel. He did not take it back to the hotel with him on his return, but planted it in a dugout. He said he used six cartridges. Asked why he took his things into the paddock, he said he owed a week’s board at the hotel, and he intended to clear out without paying for it. He knew Mo Lun at Port Pirie and it was two years since he saw him.’

Poole maintained an unnerving innocence against all the confronting, contradicting evidence, calmly reassuring his legal brief that it was Carrieton all over again, meaning everything would be fine in the end.

*

A small town in cattle country at the base of the Flinders Ranges, Carrieton was a popular, temporary accommodation hub for rail and stock workers. Almost a year to the day before Lun’s death, the body of John Moser was found lying in the yard of one its backstreet business. He had been shot in the back of the head at close range. The previous night just after midnight, people heard a barking dog followed by verbal arguments and a gunshot blast.

Mrs Joanna Wade had spoken to Charles Poole — resident of her hotel at the time — expressing a hope that the man who killed Moser would hang. A bumptious Poole told her, ‘It was good enough for the old Turk. Pity more were not put away.’ Joanna’s daughter Cecilia told police Poole told her he shot Moser. When she suggested he ‘not talk foolishly’, Poole said ‘Don’t take any notice. I am funny at times.’

Poole told police he went to bed not long after his hotel roommate Francis Naulty the night Mosur was shot. Francis Naulty told police Poole had gone out with a borrowed shotgun that night, but he was back well before midnight. Poole’s story changed after police told him witnesses had seen him on the street after 11 pm. Naulty said he could not say for certain if Poole had been out that late. Naulty could only confirm he woke next morning to find the shotgun and cartridges unmoved from he had seen Poole leave them.

Naulty had told Poole that Moser had been shot. He remembered Poole sneering that it was ‘Good enough for the black bastard hey? He won’t be showing off his wads of cash in the bar anymore.’ Naulty said he and Poole had just met. Poole had introduced himself as someone who had done some ‘dirty work before and could look after himself’. He also boasted to Naulty that ‘I’ll have a couple of hundred pounds when I go back to Pirie.’

Poole’s careless admission to Cecilia Wade saw him charged with Moser’s murder, but no forensic checks or testing were performed on the shotgun, and no spent shells were recovered from the crime scene. No money had been taken from Moser, who did make it known about town he was usually full as a bank. His bragging seemed bona fide after £25/10 in notes was found sewn into his shirt.

Unlike Mo Lun’s murder, the carrying echo of voices across the flat night landscape around Carrieton made it impossible to determine who Moser had argued with before being shot. The case against Poole proved circumstantial – the judge advising the jury they should ignore Poole’s admission to Cecilia Wade as the boasting of a witless youth trying to impress a pretty girl. The judge also considered it unlikely that even a born fool would tell someone ‘shooting Moser is why I have been so worried lately.’ An Adelaide paper reported Poole showed a nervous coolness throughout the trial, and looked unsurprised when he was discharged of the crime and released to his welcoming mother and family.

*

Translating the word Lun from Chinese can variously refer to: a wheel, a disk, a ring, even a steamship. More conceptually it can mean to take turns, to rotate by turn, or be something turning back on itself, such as a recurring event, or behaviour. Poole’s defence in the Mo Lun shooting, after the Moser dismissal, was like the young man’s folded, solipsistic thinking; in his reality the accusations against him were a set up for something he could never do. The Carrieton trial proved him eternally innocent. Poole’s sister came from Port Pirie for his Newcastle trial. She was heartbroken because of what a guilty sentencing might do to their mother – Charles was her favourite who she loved more than breathing, the blue suited boy who could never do wrong. When Charles got in to trouble growing up, he would tell their mother he didn’t do it, and that made it a new truth. As if the cosmos was in on this pathetic delusion, a Newcastle newspaper offered a prize for readers tucked daily beneath their running commentary on the Mo Lun trial; music for two songs, which are rapidly winning their way into every home: My Mother, and Sunset Trail. Unfortunately for Charles Poole, the Mo Lun jury ignored the coddled indulgence of his own imagined innocence, and the young man was sentenced to death for the murder of Mo Lun.

Charles Poole headed East immediately following the Carrieton trial. He saw it a chance to be the adventurer his father had started out as on leaving to fight in the Great War, only to return morose and beaten, with a silence that left Charles confused and angry with his father, himself and the world. Poole’s whereabouts between Carrieton and Newcastle were like his father, mostly silent except for an occasional letter or telegram home. This lacuna overlapped two unsolved shootings in New South Wales involving victims finished off with a close-range gunshot through the back of the head: one was a Russian émigré killed in Centennial Park (where no gun was found, but police put down to suicidal madness apparently brought on by him being a communist). The second involved a migrant worker in the lower Hunter Valley, whose hands had been tied roughly behind his back. The shallow grave he was buried in gave him up after heavy rain. Both men had money on the person. No reasons or suspects were followed up.

September 1941

AFTER 20 years in gaol, Charles Poole, guilty of murder near New Lambton, Newcastle, has been released by Cabinet — part of persistent effort to obtain release of a number of men who are serving life sentences, but who are declared to have become reformed, and are no longer a danger in the community. Poole shot Mo Lun, a market gardener. Why, nobody has ever been able to suggest.

Poole will be returned to another state to live with his parents. The news also allows a timely moment to reflect on the work of Detective-Inspector McCarthy (admittedly one of the cleverest officers of the State) — who as Constable McCarthy came under notice for the expert way in which he pursued his inquiries at the time.

David Murray is a university medalist with a Creative Arts Phd from Newcastle Uni. He has published two books of poetry: “Swinging from a broken clock” and “Blue bottle” (Sultana Press), and contributed to Overland, The Australasian Journal of Popular Culture and the Mascara Poetry Journal.

Murray treats historical true crime creatively as a cultural marker of everyday life. It’s a process concentrating on ordinary lives while reflecting Luc Sante’s observation that ‘violence, misery, chicanery, and insanity exist in a continuum that spans history; they prove that there never was a golden age”.

https://about.me/david.m.murray

Read more from David Murray’s Coal River True Crime Series

https://hunterlivinghistories.com/category/coal-river-true-crime/