(This post has been transferred from ‘Newcastle Government Domain’ WordPress site- originally posted 22 April 2014)

Newcastle’s King Edward Park

Local Treasures ABC1233 radio

Broadcast Notes April 2014

By Dr Ann Hardy

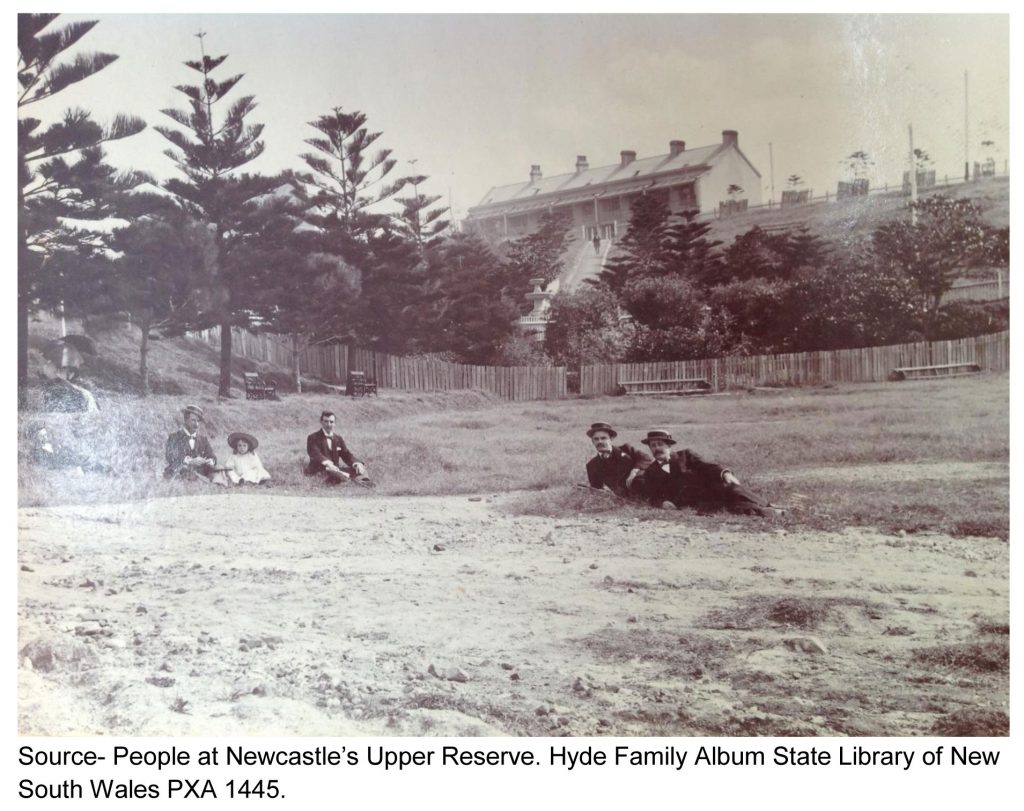

A research team interested in the history of the Newcastle Government Domain and King Edward Park meet regularly to further research of this historic precinct of the city. The group is part of the University of Newcastle’s Coal River Working Party, and includes members from the National Trust of Australia (NSW) and local community. In 2010 the group submitted a nomination to have King Edward Park listed on the NSW State Heritage Register. The following history of the park was compiled by Dr Robert Evans, Ann Hardy and research assistant Liz Thwaites for the nomination, which is under review in April 2014. The photographs of the park from the 1890s were recently located in the Hyde Family Album held at the State Library of New South Wales.

A history of King Edward Park

Newcastle Recreation Reserve, later called the Upper Reserve and after 1911, King Edward Park to commemorate the life of Edward VII, lies immediately to the south of the central city area of Newcastle, NSW. The Park is part of an historic area which stretches from Nobbys to Fort Scratchley namely Coal River Precinct, to the Government Domain (James Fletcher Hospital site) and to the Park.

The Park is roughly triangular in shape. The eastern border includes the cliffs and shoreline to the Pacific Ocean. The cliffs were once part of the Nobby’s Tuff, cream and grey layered consolidated volcanic ash that has formed above the coal seams the coal responsible for Newcastle’s existence. The northern border of the park is along Ordnance and Pit Streets: on the west is The Terrace, the Victorian street of grand mansions, and a line to Brown Street where it meets Pit Street. The western and southern borders meet near the high cliffs on Shepherd’s Hill.

King Edward Park is a creation of the nineteenth century in a city which was called, an unusual example of a transplanted British community.[1] At the beginning of the coal boom, in the 1850s there were a number of farseeing citizens in Newcastle, members of the Newcastle Chamber of Commerce, who foresaw the need for a large public park. They were very ambitious for Newcastle, it would become a great industrial area and the most important port in the Pacific, one day it might out rival Sydney. The group did much to support the shipping trade and business. The members believed that parks gave a city status. There were precedents in Victorian Britain where wealthy philanthropists fostered the creation of libraries, museums, art galleries, hospitals and public parks. They believed that their actions helped stabilize society, increased property values and boosted their images as valuable members of society. Public gardens became valued amenities in British towns and cities and the early colonists brought the sentiment to Australia. Gardens were reminders of home and a way of establishing themselves in their new settlement.

The Chamber lobbied the NSW Government for land for a public recreation area: the city was granted, in 1856, in perpetuity, the 35 acres of land (49 acres was added in 1894) which became the first part of King Edward Park “… in the most delightful and picturesque part of Newcastle from the top of Watt Street round the Horseshoe to the Obelisk”.[2] In 1863 the Newcastle Borough Council was made trustee of that area, then called the Upper Reserve.

Newcastle was founded in 1804 as a penal colony for the worst sort of convicts, the re-offenders who authorities considered deserved severe punishment. They were forced to work under the most rigorous conditions, in timber gathering, in lime burning and in coal mining. That convict era left its mark on the city in a negative self-image. However the convicts began Newcastle’s identification with coal. The commercial exploitation of coal, ‘the Black gold’ also drove the rapid growth of the port of Newcastle and between 1860 and 1890 brought prosperity to the city. The coal industry attracted immigrants from the coal mining areas of Britain, particularly Wales and the Midlands and Newcastle, NSW, became a transplanted British coal-mining village in population and in culture. However by the end of the 19th century the local mines were exhausted and mining moved inland. Newcastle slumped but its fortunes were revived with the construction of the BHP Steel works in 1913. Both World Wars brought prosperity, with periods of depression and unemployment between the wars. Then after World War II despite the closure of the steel works in 1990, there was a growing diversity of employment opportunities. People began to think about cultural matters and a regional art gallery and a museum appeared. However the basic form of King Edward Park was set in the nineteenth and early twentieth century.

The way in which the park developed was closely tied to the economic progress of a city dependent on two industries, coal and steel, which experienced periods of prosperity, stagnation and depression. There were frequent periods of unemployment and poverty which led people and local government to adopt the view that job creation was of the highest priority and industries that increased employment should be encouraged no matter how much pollution they might cause. There was little time, energy or money to direct to cultural matters. A Newcastle Chamber of Commerce pamphlet (1908) declared that ‘aestheticism must give way to the material wants of mankind …. a place so evidently intended to be a manufacturing centre as Newcastle is cannot expect to evade … the destiny mapped out for it.’ The city was a place of smoke and grime until the middle of the twentieth century. Newcastle people developed negative images of their own city which was reflected in the views of people in the rest of the country… it was not good for progress.[3]

Newcastle was additionally disadvantaged because it was dependent on outside finances. The NSW Government provided the extensive infrastructure required for the coal and steel industries and the port: they were valuable contributors to the state’s funds. However, apart from the infrastructure little of the wealth generated came to the city. Similarly, industry funding came from outside, from private financial institutions and investors in Sydney, Melbourne and London and that is where the profits went’.[4] There were no philanthropists for Newcastle amongst them. Thus Newcastle was deprived for a long time of civic amenities that one have expected in the second largest city in NSW and in comparison with other Australian, cities, both regional and capital cities. It would take until the 1970s for cultural amenities like civic museums and art galleries to become established. King Edward Park received little financial support: it is perhaps surprising it has survived so well.

The beginnings of the Upper reserve

So far we have little information on the improvements instituted in the first few decades. There were some trees planted and paths constructed and by the late 1880s citizens valued the park as a pleasant place of public recreation.

Then around 1890 Council attention was directed to increasing park facilities and appearances. The topography of the reserve presented difficulties for a prospective landscape designer. There were steep hills and deep gullies. The soil was poor. Most of the difficulties were caused by the southerly winds which were often strong and always salt laden. In most of the area only stunted grasses were growing that was how it received its first name, Sheep Pasture Hills, given in 1801 by the early explorer, Colonel James Paterson. It reminded him of English pastures.

On the other hand, the terrain offered opportunities to create a picturesque public garden. The reserve sits in a basin-shaped hollow in a coastal ridge which runs from Newcastle Beach to Bar Beach. On the northern and southern borders of the basin were prominences, 70 metres above sea level the interrupted ends of the coastal ridge, and between them a central prominence of the same height. Between the prominences were two gullies which ran from the high land near where Reserve Road and The Terrace are now, down to the sea. The northern gully was deep with steep sides. It was angled to the east and partly protected from the wind. With some care trees and plants might grow. The southern gully was shallower and more open to the sea than the northern gully, any vegetation would struggle to survive. In 1890 the Council called tenders for a landscape design for the development of the park.

Alfred Sharp’s vision

In 1890 the Newcastle Borough Council awarded Mr Alfred Sharp[5] a contract to provide a plan for the design of the Upper Reserve. The plans he produced have not been found, and our knowledge of them comes from an article in the Newcastle Morning Herald in1890.[6] James Beattie, a landscape and garden historian who is familiar with King Edward Park and with Sharp’s work has written “Today, Sharpe’s design has been altered, even though the basic structure of his conception survives” and “It… is possible to experience the winding paths and formal layout of the upper section of the reserve that adhere to Sharpe’s design principles.”[7] While many gardeners have contributed to the park’s development for well over a century and a half, one can say that King Edward Park is Alfred Sharp’s park.

Alfred Sharp was an artist, an architect and draftsman and a landscape designer. He designed other parks around Newcastle; in Islington, Hamilton, Wickham and in Lake Macquarie. He came to Newcastle from New Zealand in 1887 to join his brother, William Bethel Sharp a businessman and politician. He was born in Birkenhead, England in 1836 (d. Newcastle 1908), and trained as a draughtsman and in art. He went to New Zealand at the age of 25, worked first as a farmer, then moved to Auckland to further a career in art. He became well known as a water colourist, painting mostly landscapes which portrayed the native trees and plants of New Zealand, sometimes in their ideal state and sometimes as damaged vegetation. In highly detailed work he was expressing his love of nature and his concern that native vegetation was being destroyed by European development. Beattie describes Sharp as being amongst the best landscape artists in New Zealand in the nineteenth century.

Sharp was also an acknowledged art theorist and notorious in elite Auckland art circles for his criticisms of contemporary painting, mostly expressed in articles and letters to Auckland newspapers. His criticisms were not confined to art: he was an outspoken environmentalist, decrying the despoliation of the countryside around Auckland.

In Newcastle Alfred Sharp practised as an architect but received few commissions.[8] He continued to paint in Newcastle, often displaying his concern about the damage done to the native bush by the early settlers, in the face of government neglect. One painting showed “the last dying remnants of the tree forests that existed between Glebe and Adamstown”, emphasising dead trees and stumps amongst the few living trees His industrial scenes such as those of the Sulphide smelting works at Cockle Creek, showed ugly buildings and smoking chimneys surrounded by dying trees.[9]

In Newcastle Sharp’s paintings were less successful commercially than in New Zealand. He complained frequently about the lack of outlets for his work. More successfully he produced many illuminated addresses commemorating the visits of dignitaries and other important people. He wrote little about art but contributed many letters to the local newspapers expressing his views on the affairs of his adopted city; on social welfare, on culture, on the environment, on horticulture and on park design and management.

In landscape design Sharp had a passion for creating public spaces for people. He followed the philosophies of the English landscape designer Humphry Repton (1752-1818), a successor of Capability Brown in British gardening history. Brown, Repton and others changed the face of British gardens and parks. In their landscape designs they obliterated all the old art and geometry of gardens that had originated in France and Italy. Avenues, parterres and terraces: basins and canals disappeared and were replaced with vistas of shaped land and plantings which resembled nature. In the plantings clumps and plantations of trees predominated, their placing related to background vistas. Repton published a creed of perfection in landscape gardening: some items of which are apparent in Sharp’s ideas for the Reserve and may be seen in the King Edward Park of today. Repton declared that a park should display the natural beauties of the site and hide natural defects. It should give the appearance of extent and freedom, carefully disguising and hiding the boundaries. The whole should give the appearance that it is a production of nature only, even if the scenery has required some improvement. Sharp, like Repton and his adherents, believed that a park should be laid out in a manner acceptable to an artist, utilising the skills of a gardener. In Newcastle Sharp continued to bring his views to public notice.

The Newcastle Morning Herald published over fifty letters from Sharp; his forceful and colourful language must have appealed to the editor. He wrote angrily about the pollution of the beaches of Newcastle and the rubbish that people left lying on the streets. He complained about the lack of a sewerage system in the city. He was concerned about conditions of the working class people in the grim industrial climate of the Newcastle. He deplored the cultural poverty of the middle class … the city lacked a museum, an art gallery and any art society.

Sharp was conscious of the living environment, the trees and plants, in and around a city. He criticised the bareness of Newcastle,

If ever cool, green shade would be appreciated it would be in the glare and heat of our dusty streets—such a desirable thing can be attained with but little cost, and only requiring some care and attention while the trees are young, it is a standing wonder both to residents and strangers, why Newcastle streets are so hideously bare of public trees.[10]

He complained that even the few existing trees were treated badly by those who were meant to care for them. He loathed excessive pruning “the knife and saw rampant beyond all conception”.

Sharp was distressed by the way trees were managed in the Upper Reserve and in other parks around Newcastle. He knew from his experiences in New Zealand that growing trees in adverse conditions, with exposure to the wind and a salt laden atmosphere was fraught with difficulty. Trees planted in such areas needed careful protection if they were to flourish and if they were to maintain the attractive appearance essential in a public pleasure ground. He stated that trees should be planted in clumps for mutual protection. Salt resistant shrubs could be planted around them to lessen the impact of the wind. To the tree every branch, every twig and every leaf was important ‘outrageous pruning’ was so damaging. Sharp also appreciated the importance of the soil around the trees for successful growth. He condemned the common practice in the Reserve of digging the soil near the trees for tidiness or for growing flowers. Digging severed the surface roots which were important to the growth and vitality of trees, depriving them of moisture and nutrients. Digging diminished the structural support trees needed to defy strong winds. The practice of burning off the grass and leaves under the trees horrified him even more than the use of the spade, because it damaged the surface roots and burnt the leaves.[11]

Sharp was not totally opposed to flower gardens in parks, but was adamant that they should not be planted near trees. He also argued that annuals required much effort and expense to maintain an attractive appearance and their beds were bare for a large part of the year for cultivation and replanting. Planting trees and shrubs offered a more effective way of creating a pleasing environment in a public park: they should be the first priority in planting .Grass could be allowed to grow near the trees, it would not harm them and conserved moisture. Sharp wrote about the harmful practices he had observed in the Reserve. In a letter headed “Woodman, spare that tree” he wrote that the mistreated trees often ended up “as pitiful objects of misery and ugliness; and surely, a broom stick is not a type of tree.”[12] Trees could be trimmed to allow people to walk under them as long as the branches were not disfigured and distorted. He believed that the provision of shade trees was essential. For example, he complained that the circular lawn in the Reserve would be barren and shade less if the Council proceeded with its plans to build a Rotunda. The report from Council stated “They should plant a circle of giant myrtles (pohutakawa) so that people could sit in the shade and listen to the band of the 4th Regiment”.[13]

For Sharp trees were the most valuable adornment for a scenic park. A landscape designer should select carefully the varieties of trees to ensure that they flourished and grew decoratively. He said he was sick of some of the trees commonly used in sea side parks in Australia. The Norfolk Island pine (hereafter pine) was ugly and spiky and grew too slowly it would be no good in a pleasure garden. Today he might be surprised to see how well the pines in King Edward Park have grown and how well they suit the large scale of the park and its background). Moreton Bay figs were also unsatisfactory: they kill everything beneath them and cover the ground with litter and debris.[14]

Sharp strongly advocated planting the pohutakawa, the giant myrtle of New Zealand (Metrosideros excelsa, the NZ Christmas tree) because it survived in coastal conditions, it grew to 30 metres, was evergreen and had a handsome spreading crown for shade. It did not create litter. In summer it was covered with attractive red flowers.[15] Pohutakawa trees grew well near the coast in Newcastle, including in King Edward Park, although rarely reaching the heights attained in New Zealand. Unfortunately, from the 1980s, the trees planted in the park and on The Hill began to succumb to a so-far undetermined disease.

Many pohutakawa were planted in the Reserve, many imported by Sharp himself (he recommended 800 in his plan). He stimulated a brisk trans-Tasman trade in these trees and others which he believed would flourish here. In both NZ and Australia Sharp supported the preservation of the native vegetation, but had some unexpected exceptions. He expressed distaste of Australian eucalypts perhaps they did not suit his ideas of an artistic tree. Given his views on the value of preserving native vegetation is surprising that in Australia. He became a champion of exotic New Zealand trees. Perhaps, having observed the extreme conditions in the Upper Reserve he advocated for trees which he was confident would survive and present an attractive appearance. This understanding was based on his knowledge of their success in similar conditions in New Zealand.

Sharp wrote often about the importance of paths in a public park, a network allowing easy access to all parts of the grounds. For an interesting stroll they should be winding with easy grades and wide enough for companionable walking; they should provide access to both the formal sections and to those parts of the park which might be left as ‘wild nature’. Sharp had great faith in the restorative powers of nature that such a park would provide.

One can also see that, to a believer in Repton’s philosophies of landscape design, how exciting a challenge it was for Sharp to have an opportunity to plan a garden for such a site as the Upper Reserve. Contemporary writers in the Newcastle Morning Herald strongly approved of his plan. His knowledge of horticulture and his awareness of the problems of gardening in adverse conditions and the ways of dealing with those problems gave him valuable skills to manage the Reserve. It is unfortunate that he was not given the opportunity to contribute more to the early establishment and development of the Upper Reserve.

How the Park Developed

The following examines how the park developed. The many phases of use are discussed as well as particular areas of the park that had a specific purpose.

King Edward Park Headland Reserve is the name given recently to an area of now level land at the top of Watt Street on the prominence on the northern edge of the park. This area of the park is relatively small and was a part of the original grant of land. It offers a great overview of King Edward Park, has been open to visitors and is socially and culturally a significant part of the Park. The area has also been of special significance to the Aboriginal people of the area. The headland, Yi-ran-ni-li means ‘the place of falling rocks’ reflecting Dreamtime stories of Awabakal people.[16]

The headland became the site of a coal mine, one of the first in Australia. It was probably established by 1817 but perhaps earlier, and continued to the 1830s. The position of the shaft is unclear there has not been a thorough archaeological or heritage assessment of the site to investigate the location. The deep shaft was worked by convicts who carried coal down the hill to the harbour on a wooden railway which ran down along a track which became Watt Street. The mine was later operated commercially by the AA Company (Dates unclear). From 1887 the Borough Council used the mine shaft to dispose of night soil from the city. Accumulation of gases and a workman’s lamp caused a loud explosion and much alarm to those living the prestige of The hill.[17] In the same period seepage of night-soil contaminated water from the mine shaft caused pollution of the marshy ground at the bottom of the northern gully (see later)

The Headland was also known as home to a prosperous bowling club and has extensive views over the ocean and shoreline cliffs. There was little development on the headland site until the Newcastle City Bowling club was given a lease in 1890. Over 115 years the Club land constructed three greens and two tennis courts. To level out the site for recreational use the ocean end (east side) required 4000 yards of the land to be filled. A small club house was built on the west side of the lease but was later moved to the south side and progressively enlarged. There were complaints that in these processes public land had been alienated and given to a small exclusive group, but to no effect.[18]For financial reasons the bowling club collapsed. Attempts by various groups, including a commercial enterprise failed to revive the club. In 2005 the government revoked the lease and under regulations relating to the use of coastal reserves opened the headland to commercial development. In 2013 the buildings have been demolished and the area is out of bounds and fenced. Headland reserve has been the subject of disputes between a developer, Newcastle City Council and community groups.

The Northern Gully- upper section above The Horseshoe

As mentioned earlier immediately to the south of the headland is the northern gully, which begins near the junction of Reserve Road and Bingle Streets. In its natural state the gully drained the surrounding hills into an intermittent water course which ran down between steep slopes to spill over the cliffs onto the rocky ocean shelf. This gully is the most developed part of the Park.

However well before the park began the gully had been used for recreation. In the 1820s Major Morisset, the Commandant of the penal settlement, frequently walked from his quarters at Government House in what would now be Fletcher Park up the hill to the headland and down across the gully to the Bogey Hole. The Bogey Hole is an ocean swimming pool dug by convicts under control of the Commandant. Apparently Morisset was “fond of sea bathing”.[19] The path he took was referred to as The Horseshoe. This track was progressively upgraded for foot traffic, for horse and carriage and for motor cars in the twentieth century. It has become a roadway but many people continue to name the as The Horseshoe, a landmark of King Edward Park.

The Cricket Ground

In 1890 the higher part of the gully was leveled. It was called the ‘Cricket Ground’ and used. It continues to be used for many leisure activities, including informal games, for picnics and from time to time for concerts and cinema performances. Below the land slopes steeply to the next leveled area, the rotunda lawn. Between the two areas there are plantations of pines which extend around the rotunda lawn. This is where the first plantings took place in the park and where there were attempts to find the most useful trees and shrubs. In the plantation there is the Fountain. Unlike many city parks in Australia King Edward Park has very few monuments. In 1879 the fountain was first, in 1879, placed in Scott Street outside Newcastle Railway station, partly because it was one of the few places in Newcastle with reticulated water. It was described as having drinking troughs for dogs, cattle and horses. It is an imposing monument, more than two metres high and one metre across with several basins and drinking spouts. Its origins are unknown. After reconstruction it was moved to its present site in the Reserve in 1888. It has unfortunately been the object a number of incidents of vandalism. From the fountain area a number of paths radiate, up to Reserve Road, several to The Terrace and up the hill to York Road. The paths reflect the design philosophies of Alfred Sharp. Below the fountain is the curve of York Road‘ which runs around the western end of Rotunda Lawn, curves around the central prominence then around the western end of the southern gully up to the exit gates at the top of The Terrace.

The Rotunda Lawn

The Rotunda lawn, which was constructed in the 1890s, is the main ceremonial area on the park. It is a level area of lawn surrounded by steep banks in which now large trees, mostly pines and a few figs have grown to a very large size. In the centre is the Rotunda, “a classic example of a late Victorian structure with its finely moulded iron roof and cast iron lace, placed in an English garden setting”.[20] It was built in 1898 and was used for brass band concerts. Rotundas and brass bands have a particular significance for Newcastle, NSW, because in the second half of the 19th century it had a large British born population. British custom came to Newcastle, in the naming of many suburbs, in culture and recreation and in the creation of brass bands and the building of rotundas. Brass bands were a creation of early Victorian Britain. In that period brass musical instruments were becoming affordable for members of the working class who were beginning to experience leisure from work. They could afford and were free to perform their music. Brass bands flourished, specifically in the coal-mining areas of the Midlands. Rotundas were built for public performances and competitions were held between the many bands formed. Apart from their leisure bands were seen a socially desirable. The tradition came to Newcastle: Plans for a rotunda in the Upper Reserve featured in a number of park plans, including those of Alfred Sharp.[21]

Until the opening of Civic Park in 1937, Newcastle held its main civic occasions, the festivals, the welcoming of visiting dignitaries, Anzac Day ceremonies and other celebrations on and around the Rotunda lawn. Perhaps the most momentous event occurred in 1911 to mark the coronation of George V. After a day of street marches 20,000 people gathered in King Edward Park to sing the national anthem and other patriotic songs. Today the lawn used for play, for picnics and for weddings.

From the Rotunda lawn steps descends a short terraced slope where there are several varieties of trees, perhaps examples of those trees tried in the park and growing here with varying success. There is also maintenance and workmen’s sheds. Then there is the curve of The Horseshoe which encloses a deeper part of the gully running down to the cliffs

The northern gully – Lower section below The Horseshoe. In shaping this part of the Park one perhaps might have expected those responsible to have taken greater advantage of the spectacular terrain, the deep gully with its water course, the steep sides and in the distance the cliffs and the expansive ocean, a vista for an artist. There were problems in gardening here, the steep slopes and the salt laden winds, although this was as better protected area than other parts of the park. There was also the problems of drainage, water normally ran into the sea but was often impeded by silt. The gully drained the surrounding hills and then when houses were built on the hill there was more storm water and even sewerage at times. Storm water from the streets is still piped under the western part of the park into the gully. There was also the period around the 1887 when night soil dumped into the mine shaft on the bowling green site contaminated the water seeping into the gully. Apart from the unpleasant odours citizens were concerned about the health risks.

There were other drainage problems to be dealt with. With swimming becoming popular, the Council enlarged the Bogey Hole in 1884 and wanted to make it more accessible from the city. A path was constructed from Newcastle beach along the base of the cliffs and another down from Watt Street. To allow the flow of water bridges were built over the two water courses, the one from the northern gully and the other that curves around the middle prominence from the southern gully. In the 1930s there was the extension of Shortland Esplanade to the Bogey Hole, a road which had to be built up with filling, which again interfered with drainage. Sumps were dug and water piped under the road to carry it to the cliff, but siltation was and still is a problem.

In his plans Alfred Sharp had an ambitious plan for the low northern gully. He designed ta series of three dams each 10 feet high and 80 feet long and 10 feet deep at the lower end. They formed three ponds a half to one and a half chains long and thirty five feet wide. They would be stocked with fish and planted with water lilies. The southern protected side of the gully would be “thickly planted with hanging woods … with paths winding in and out amongst the trees…that is, if the right kind are planted.”[22] Sharp recommended the pohutakawa.

However despite the opportunity offered, a later gardener chose to create flower beds in the gully in ‘U’ of The Horseshoe. Although flower beds were conventional decorations in many Victorian parks, the result would not have pleased Sharp, it was not natural, In the 1920s after filling with large amounts of soil the resulting level area was planted with lawn and ten separate flower beds created. They have long provided a bright display of annuals for short periods each year interspersed with long periods when the beds are largely bare. They require much labour for maintenance, an increasing problem in times of Council austerities. These are the Garside Gardens named after an earlier head gardener.

Below the Garside Gardens as the gully slopes down much effort has been spent in dealing with the problems of the drainage as well as trying to make the area attractive and accessible to the public. Recently the Council has created an artificial water course lined with large boulders and in its course built several storage ponds. Reeds and other water plants have been planted. At the lower end the soil is still marshy, although the flow of water is moderated. Here it has been planted with native grasses, shrubs and trees. There is then a large sump to catch water and convey it by pipes under Shortland Esplanade.

In 2004 this sides of the lower part of the gully were further modified by terracing and by filling, processes which were severely criticised, because they changed the natural appearance. It was a convenient step for the Council. The nearby cliff overlooking the Bogey Hole had to be reduced in height to reduce the risk of boulders falling into the pool. The spoil from the excavation, the rocks and soil, was dumped into the gully, a cheap method of disposal. This action prompts the need for a proper plan of development for King Edward Park, and reminds us that such a plan has never been produced.

The southern gully

The southern gully is wide with gentler slopes than those of the northern gully. The mouth is widely open to the ocean so that it is a windswept area. It also has an intermittent water course flowing down it but now there is only a soakage area at the bottom. From here accumulated storm water is carried under York Drive to a small ravine which runs northwards, between the middle prominence and a cliff-side ridge, to near a sump near the Bogey Hole where it enters the sea via a pipe. In this ravine the flow of water is slowed and absorbed by a mixture of natural and planted native shrubs and grasses, which are now growing strongly, reducing erosion. Their vigorous growth demonstrates the benefits of the protection provided by the adjacent seaward ridge. Before human intervention the outflow from the southern gully flowed down this water course to enter the sea not far from the outflow of the northern gully.

The main southern gully and the surrounding hillsides are mostly covered with native grasses, largely Themeda australis, a short, clumping reddish green grass. Before European settlement this grass was widely distributed along the NSW coast. Now in King Edward Park there are about four hectares of it and one of the few areas left in NSW and thus of heritage significance. There is the occasional stunted tree the results of earlier plantings, and under the protecting brow of the top of Shepherds Hill on the southern wall of the gully a group of trees and shrubs and grasses, Acacia sophorae, Banksia integrifolia, Westfringia ruiticosa and Lomandra longifolia have been planted. They are growing well and are self-seeding, reflecting their protected position, their planting in dense clumps and that they are native to the coast. At the top of the gully, along The Terrace is a row of well-grown palm trees in their position they are partly shielded from the wind as well as having a degree of salt tolerance. Apart from the plantings mentioned and roads and paths (the Bather’s Walk crosses it) the southern gully has been little developed. It attracts walkers, children and free-roaming dogs.

At the top of the southern gully, where York Road enters The Terrace are two sand stone pillars, all that remains of the four pillars and ornate wrought iron gates which marked the original entrance to the reserve at the top of Watt Street. With the coming of motor cars that position proved dangerous, they could easily run over a cliff. The gates were moved further up Ordnance street and then to their present position. Mr Joseph Wood, a brewer and prominent citizen, donated the gates in 1907.

Arcadia Park

Arcadia Park (it was given that name to honour an American sister city) is and always has been part of King Edward Park, although separated from the main part by road, Reserve Road and the continuation of Wolfe Street . The park is a small triangular parcel of land to the west of Wolfe Street. It is an area where plants will thrive because it slopes downwards away from the prevailing winds but has largely been neglected until the 1970. For a time it contained a quarry. Alfred Sharp suggested only planting trees there but no other improvement, they would come later. However in 1978 the Newcastle Council landscaped the area and planted a large number of trees, which have flourished. It is an area which is little used but could be a valuable adjunct to the main park.[23]

The Bogey Hole

The Bogey Hole, the ocean swimming pool in King Edward Park, sits in the rock shelf below the cliffs at the bottom of the northern gully. Convicts gouged the pool out of the rocks on the ocean shelf in about 1820 for the personal use of Major Morisset, the Commandant of the colony of Newcastle from 1818 to 1823. The pool was first called Morisset’s or the Commandant’s baths but later the Bogey Hole, a name believed to be related to an aboriginal term ‘to bathe’. There have been suggestions that the excavations made use of a previously existing cavity in the rocks, perhaps made by aborigines, but there is no confirmatory evidence.

In the 1850s an English traveller, John Askew visited the Bogey Hole on several occasions for a swim. “I have stood upon these rocks and listened to the hoarse voice of the ocean, while lashed into fury by the north-east wind, and have been awed by the thundering sound of its seething waters, as I never have by any of the awe-inspiring phenomena of nature. The feelings awakened by this majestic scene are indescribable: and I never stand on any spot which so heightened the impressiveness of a scene so terribly sublime”.

In 1863 the Newcastle Council assumed control of the Bogey Hole and made the pool accessible to the public, but at first only by males. It became the most popular site for sea bathing in Newcastle. Newcastle was endeavouring to acquire an image of a holiday resort. In 1884, responding to public demand for more facilities for safe sea bathing the Council enlarged the Bogey hole to about seven times of its previous size, still irregular in shape and approximately 105 feet long and 50 broad and sloping from five and a half feet deep to three and a half. Steel stanchions and chain were placed on the ocean side for safety. The surroundings of the pool were tidied and access to an almost inaccessible place improved by cutting broad steps in the rock. In the cave in the cliff behind the pool better provision was made for changing where a caretaker provided clean towels. “The Bogey hole has been metamorphosed into one of the finest swimming baths in NSW, we might almost say, about the finest in Australia, and challenge contradiction.”[24] In 1911 after receiving a petition from 199 women, the Council permitted women to use the baths on certain days of the week.[25] Over the years changing rooms have been built above the pool and on the entrance path, and demolished, sometimes by falling boulders.

With their increasing popularity the City Council made it easier to get from the city to the Bogey Hole a path with a series of steps was formed from the Reserve near the Hospital for the Insane down to a path running over two bridges across the mouth of the northern gully. Past the Bogey Hole the path, a sidling track continued along the cliffs to what was known as the gulf bathing place.[26]

The Bogey Hole is one of the earliest visible artefacts of European occupation in Newcastle. It is still used by bathers and much visited by tourists. It has recently (June 2013) been refurbished.

The Shepherds Hill defence installation

On top of Shepherd’s Hill to which the name Khantarin has been applied, on the southern boundary of King Edward Park, is the heritage recognised defence installation. It contains the remains of a sunken gun emplacement for a 9-inch disappearing gun, and related range finding bunkers dating from 1890. They were constructed to meet fears of Russian incursion. At the same time the Gunner’s Cottage, which now house the Marine Rescue group was built to accommodate the troops who manned the gun. The other prominent structure is the reinforced concrete tower which was built in the early 1940s to defend the port of Newcastle against Japanese attack. The tower, now disused, included the control post for a string of defence positions which extended from Port Stephens to Redhead. It also had observation and communication functions and there was a large radar antenna on the roof. There were two guns mounted nearby; a 6 inch gun emplacement on the cliff on Strezlecki Lookout, and an emplacement of the central prominence in the Park. On the cliff below the bowling-green site was a concrete searchlight bunker and behind it the engine room which housed the generator for the light remains of both still exist.

The Shepherds Hill defence offers existing evidence of changing approaches to the land’ based coastal defence systems in NSW. The site is used often for picnics and wedding parties. The Bathers Track which runs through the site brings many visitors.

The Obelisk Hill

The Obelisk Hill is situated on the northern edge of King Edward Park. It was originally contiguous with the rest of the main park area but was separated by the construction of Reserve Road in the 1880s. On the other sides of the Hill are Ordnance Street and Wolfe Streets (extended in 1870s). Inside the triangle of roads the Obelisk Hill is surrounded on three sides by rocky cliffs, which emphasis its height which provides 360 degree panoramic views of the city, the ocean and the rest of the Park. On the top is the Obelisk, a typical tapering monolith. It was built in 1850 to commemorate the Government Flour Mill, a brick and stone structure, a windmill, with huge Dutch sails, which was built in 1820 at the instigation of Major Morisset the commandant of the penal colony. There was shortage of food in the colony and while he did not want to reward the convict by providing too much food, they had to have sufficient to mine the coal without getting sick or dying. The mill met the needs until flour became available from other sources in the Hunter Valley. The Mill, with its height and distinctive shape became a valuable navigation aid for mariners entering the difficult passage to Newcastle Harbour. When the mill was demolished in the 1850s, as obsolete, on orders from the Government in Sydney navigators and ship owners demanded a suitable replacement so the Obelisk was built. Despite lightning strikes and earthquakes, the Obelisk remains today as a tourist attraction and a reminder of Newcastle’s harsh convict origins and of the importance to Newcastle of shipping and the coal trade.

The park is an amazing part of our coastline, and unique because of its diverse heritage. Today it continues a much loved place to spend time with friends and family, a short walk from urban spaces and a park that has many stories to tell.

Sources

Albrecht, Glenn. “Yi-Ran-Na-Li: A Cliff Face at Newcastle South Beach.” <http://healthearth.blogspot.com.au/search/label/Yi-ran-na-li>.

Beattie, James. “Alfred Sharpe, Ruskin and Australasian Nature “The Journal of New Zealand Art History27, (2006).

Bingle. Past and Present Records of Newcastle. Newcastle: Bayley & Son & Harwood, Pilot Office, 1873.

Docherty. Newcastle the Making of an Australian City. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1983.

G.B.Grimm. History of Newcastle City Bowling Club 1809-1939 Newcastle: The Club, Unknown.

Metcalfe, A.W. Metcalfe and Andrew. “Mud and Steel: Thee Imagination of Newcastle.” Labor History 64, (1993).

Reedman, Les (2008) ‘Early Architects of the Hunter Region: A Hundred Years to 1940′.

Vagabond, The. “At Newcastle ‘the Vagabond’.” The Sydney Morning Herald, 27 February 1878.

[1] Docherty, Newcastle the Making of an Australian City (Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1983).

[2]Bingle, Past and Present Records of Newcastle (Newcastle: Bayley & Son & Harwood, Pilot Office, 1873).

[3]A.W. Metcalfe and Andrew Metcalfe, “Mud and Steel: Thee Imagination of Newcastle,” Labor History 64 (1993).

[4] Docherty, Newcastle the Making of an Australian City.

[5]Alfred Sharpe sometimes added an ‘e’ to his name.

[6]Newcastle Morning Herald, Newcastle Morning Herald 27 August 1890.

[7]James Beattie ‘Alfred Sharpe, Ruskin and Australian nature’ The Journal of New Zealand Art History, 27, 2006, 38-56.

[8]Les Reedman, ‘Early Architects of the Hunter Region: A Hundred Years to 1940′.

[9]James Beattie, “Alfred Sharpe, Ruskin and Australasian Nature

” The Journal of New Zealand Art History 27 (2006).

[10]Newcastle Morning Herald 18 March 1889.

[11]Newcastle Morning Herald19 November 1891.

[12]Newcastle Morning Herald19 February 1892.

[13]Newcastle Morning Herald26 February 1892.

[14]Newcastle Morning Herald7 September 1891.

[15]Newcastle Morning Herald, 12 August 1891.

[16]Glenn Albrecht, “Yi-Ran-Na-Li: A Cliff Face at Newcastle South Beach,” <http://healthearth.blogspot.com.au/search/label/Yi-ran-na-li>.

[17] Maitland Mercury 21 January 1888

[18]G.B.Grimm, History of Newcastle City Bowling Club 1809-1939 (Newcastle: The Club, Unknown).

[19]Bingle, Past and Present Records of Newcastle.

[20]Jeans and Spearitt

[21]Docherty, Newcastle the Making of an Australian City.The Vagabond, “At Newcastle ‘the Vagabond’,” The Sydney Morning Herald 27 February 1878.

[22]Newcastle Morning Herald, 29 August 1890.

[23]Newcastle Morning Herald 17 November 1978.

[24]Newcastle Morning Herald 22 Dec 1894

[25]Newcastle Morning Herald 11 Feb 1911.

[26]Newcastle Morning Herald 18 June, 2 September, 18 November 1884

My maternal grandfather, Robert Benjamin Petherbridge used to tell us that he and his mates would attempt to disrupt the brass band concerts in the King Edward Park band stand by sitting as close as possible to the front row and suck lemons. This was apparently a favourite prank undertaken by young larrikins. My grandfather was born in January, 1892 and belonged to the family which owned New South Wales Aerated Water and Confectionary Company.

Re: the entrance gates donated by Joseph Wood . 1. The two inside pillars are not present at Shepherds Hill entrance any more ? 2. The outside pillars grace a home in Croudace Street, Lambton – on the corner of Floralia Close. Apparently the council manage owned the house there, so its not clear case of “stolen”… he would have been in a position to get it authorised